0. Why wasn’t I posting for some time#

It’s been almost a year since the last post. It was actually a super busy time as we were closing on two very important milestones - first we released a co-op mode of Forever Skies on 9th of December - it was a culmination of my work on the game, as my project-long task was creating TPP animations to match them to FPP ones. It was the last patch before the release, so after a quick Xmas - New Year break we were back working on the final release that happened on April the 14th!

Due to the workload I had to actually drop side projects such as this page. After a break, as we’re working on the Post-Launch Support, I finally found both time & motivation to start working on some small stuff and as I’ve been moving towards my goal of becoming a much more technical animator. It seems like there isn’t a better post to start on than by doing some python scripting. Before Idive into how I’ve written a script that creates a game-ready skeleton hierarchy out of the bones, I wanted to talk why I’ve chosen the topic.

There are actually two different reasons on why I’ve started thinking about this type of tool - first one is that I finally found time to start reading Technical Animation in Video Games by Matt Lake (that needs it’s own post when I finally finish it) that talks a lot about automation in the rigging department. The other one is a task I was given that I couldn’t finish in time - as I felt defeated, the task lived rent-free in my mind, so I’ve decided to tackle it during a weekend and I’ve found out that it isn’t that complex! That spark inspired me to start a new Markdown file and write a post to share the knowledge I had acquired! Of course I am not a professional programmer, so I am going to explain stuff as someone who is learning python & programming.

Let’s go!

1. Foreword#

In this article you’ll learn:

- How does a game ready skeleton hierarchy look like

- How to write a simple script to operate on bones in blender

- How to write a script that builds a game-ready skeleton hierarchy using Python

2. Quick reminder on Skeletal Mesh & Hierarchy#

What is a skeletal mesh?#

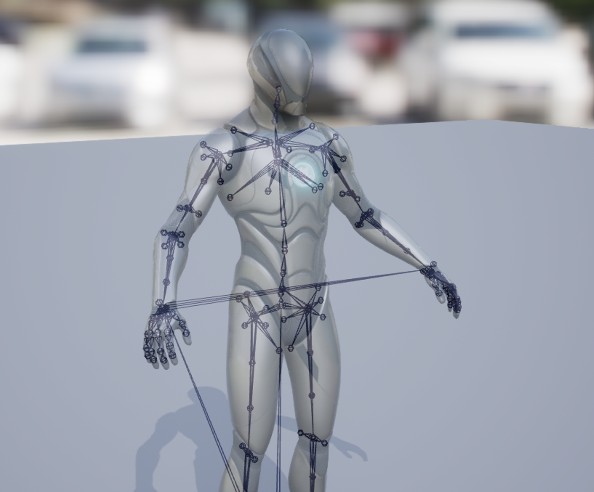

As game animators, we work with Skeletal Meshes everyday. In engine, a skeletal mesh (SK_), is an object that holds information about a 3D model with a skeleton that is skinned. It consists of two main parts:

- Mesh - is the visible geometry of the character or object

- Skeleton - is a hierarchical set of bones that control how the mesh moves and deforms during animation (hence why the mesh is “skinned” to the skeleton)

SKs are used for anything that requires complex movement or deformation such as characters, creatures and sometimes machinery. In Unreal Engine they’re utilized in Animation Sequences (imported animations), Animation Montages and Animation Blueprints.

If you ever exported a character from blender or Maya, you might recognize that you only export the bones usually called SKL_ (skeleton_) or JNT_ (joint_) usually used in Maya or def_ (deform_) used in blender by selecting both the skeleton and the mesh of the character. It is the basic building element of a character’s rig, on top of which we build the controls.

Game-Ready Skeletal Hierarchy#

A standard skeletal hierarchy starts with the root bone, that is going to hold information on the main bone of the skeleton - the hips.

After that, the biggest building block of a character is it’s spine. UE4’s Manny uses 3 bones to hold the information about game character’s spine and it’s of course a child of hips. As spine03 is usually around character chest, it becomes a parent of the neck and head bones.

From the chest, we of course have arm bones. They have to be attached to chest, so naturally we are going to parent them to spine03. To give animators a good control of the arm, we’re going to start with the clavicle that is going to act similar to a collar bone.

One of the most important parts to remember is that arms (and legs) are actually mirrored on the side, so we have to actually use a prefix or suffix to differentiate them. I am going to use a _l or _r suffix.

In UE we mostly use 3 bones for each finger, making our hierarchy look like this:

root

hips

spine01

spine02

spine03

neck

head

clavicle_l

arm_l

forearm_l

hand_l

pinky01l

pinky02l

pinky03_l

ring01_l

ring02_l

ring03_l

index01_l

index02_l

index03_l

point01_l

point02_l

point03_l

thumb01_l

thumb02_l

thumb03_l

clavicle_r

arm_r

forearm_r

hand_r

pinky01_r

pinky02_r

pinky03_r

ring01_r

ring02_r

ring03_r

index01_r

index02_r

index03_r

point01_r

point02_r

point03_r

thumb01_r

thumb02_r

thumb03_r

thigh_l

calf_l

foot_l

balll_l

thigh_r

calf_r

foot_r

ball_r

I’m going to use that as basis for the today’s topic.

3. How do you actually parent bones with script in blender?#

Assumptions#

For starter’s I am going to assume you know how to create a simple armature in blender and you’re comfortable with blender UI. You also have knowledge of basic scripting using blender logic. To write scripts there are many different tools - from the in-blender Text editor, to full Python IDE.

Understanding the task#

There’s an armature with hierarchy:

bone1

bone2

bone3To write the script, I first had to understand what exactly I am going to achieve. If I was doing it by hand, I’d start by doing this:

- Select the Armature in viewport and switch to Edit Mode

- Select

bone2, thenbone1, CTRL+P -> select Keep Offset - Select

bone3thenbone 2and repeat

This is basically the list of operations I want to achieve by code.

To actually automate this process, let’s create a new function called simple_bone_parenting, and tackle issues step by step.

Selecting the armature and switching to edit mode#

The first problem I’ve had to tackle is actually going to switch Armature to EDIT MODE, as that’s the only mode where you can manipulate bone hierarchy.

def simple_bone_parenting():

# grabs the context of a selected object

armature = bpy.context.view_layer.objects.active

if armature and armature.type == 'ARMATURE':

bpy.ops.object.mode_set(mode='EDIT')There isn’t much to explain; I’ve used blender python API docs to store the selection in armature, then switched it to Edit Mode after checking if it exists and if it’s an armature.

Selecting bones and making them a list#

The next part is creating a simple parenting method using if statements. That was my first idea on how to tell python what kind of hirarchy I want. After all, every child in hierarchy can only have one parent, so the if statement shouldn’t be that scary, right?

def simple_bone_parenting():

armature = bpy.context.view_layer.objects.active

if armature and armature.type == 'ARMATURE':

bpy.ops.object.mode_set(mode='EDIT')

# create a list of selected bones

bones = armature.data.edit_bones

for bone in bones:

# ensure the name matches the string

bone_name = bone.name.lower()

if bone_name == "bone1":

# bone1 is the root

bone.parent = None

elif bone_name == "bone2":

bone.parent = bones["bone1"]

elif bone_name == "bone3":

bone.parent = bones["bone2"]

I’ve created a list called bones which hold values of selection, in this case bones = ["bone1", "bone2", "bone3"]

Next, to ensure that the bones are named properly I’ve changed them to lowercase, and created a simple if statements.

There are two interesting things:

- First of all,

bone1has a parent ofNoneas it’s the root of the Armature. - Rest of the parents follow an idea that looks exactly like the manual method -> pick a bone (eg.

bone1), use functionbone.parent, select parent bone from the list (eg.bones["bone1"]) - that’s probably the same thing that is happening “under the hood” of the hotkeys.

With that, I’ve actually managed to write a script that can easily create a simple bone hierarchy that I’ve predefined. That’s the a-ha moment I was talking before - the one that made me realise I can write this automatic bone hierarchy script.

4. Building game-ready skeletal hierarchy with a script#

Building MVP#

As this is still new territory for me, I’ve decided to build the script from the MVP (minimal viable product) and then scale it up, so I’ve created a simple, one side bone hierarchy like this:

hips

spine1

spine2

spine3

neck

head

clavicle

arm

forearm

wrist

thigh

calf

foot

ballAs there’s basically no difference to the previous script, I’ve created a new function called create_skeletal_hierarchy() and updated the ifs:

import bpy

def create_skeletal_hierarchy():

armature = bpy.context.view_layer.objects.active

if armature and armature.type == 'ARMATURE':

bpy.ops.object.mode_set(mode='EDIT')

bones = armature.data.edit_bones

for bone in bones:

bone_name = bone.name.lower()

# create spine

if bone_name == "hips":

bone.parent = None

elif bone_name == "spine1":

bone.parent = bones["hips"]

elif bone_name == "spine2":

bone.parent = bones["spine1"]

elif bone_name == "spine3":

bone.parent = bones["spine2"]

elif bone_name == "neck":

bone.parent = bones["spine3"]

elif bone_name == "head":

bone.parent = bones["neck"]

# create arm chain

elif bone_name == "clavicle":

bone.parent = bones["spine3"]

elif bone_name == "arm":

bone.parent = bones["clavicle"]

elif bone_name == "forearm":

bone.parent = bones["arm"]

elif bone_name == "wrist":

bone.parent = bones["forearm"]

# create leg chain

elif bone_name == "thigh":

bone.parent = bones["hips"]

elif bone_name == "calf":

bone.parent = bones["thigh"]

elif bone_name == "foot":

bone.parent = bones["calf"]

elif bone_name == "ball":

bone.parent = bones["foot"]

# automatically reset to Object, to see changes in outliner

bpy.ops.object.mode_set(mode='OBJECT')

create_skeletal_hierarchy()

There are a few notes - first of all this looks super ugly. My first though was to use a switchcase (I’ve had most of my programming knowledge in C after all), but I’ve learned that Python didn’t have a

swithcase implemented until PEP06341! That was actually shocking, as I’ve always though of Python as this high-level, easy-to-read, beginner-friendly programming langauge.

Said change implemented a match-case that works similarly, but as I’ve started an internet sleuth to find another resolution to this case, I’ve found something better, that I am going to explore next.

Besides the obvious, I’ve also added a mode_set, to see the differences in Outliner right away.

If you run this script, the Armature hierarchy is going to look like this:

hips

spine1

spine2

spine3

neck

head

clavicle

arm

forearm

wrist

thigh

calf

foot

ballAt this point I knew, I can actually make it work pretty well.

Dictionary for the rescue!#

As I was looking through the web, I’ve also sent a question to my friend, who’s actually a programmer, if there are any tricks to make this prettier than this myriad of ifs, as for now there are 14 different if statements and if the skeleton was mirrored, it’d be 22!

Why dont you use dictionary?

That was basically the first answer I’ve got. I haven’t used dictionaries before, so I went straight to documentation, to understand what it is and how can it help me.

Let’s start by saying, that the dictionary is a simple data structure, an array basically, that instead of being indexed by range of numbers, are indexed by keys.

In my understanding for this case, dictionary is basically an array, where I can store an unique key:value pair, which looks suspiciously close to our ifs.

So how does it work?

Let’s define a dictionary called my_dictionary, that is going to hold three pairs of data:

blenderis adccunrealengineis anenginepythonis alangauge

my_dictionary = {

"blender": "dcc",

"unrealengine": "engine",

"python": "langauge"

}Now, we can print, a simple sentence, using it:

print(f"""I use blender as my {my_dictionary['blender']},

Unreal Engine as my {my_dictionary['unrealengine']},

and python as my programming {my_dictionary['python']}""")Outputs: “I use blender as my dcc, Unreal Engine as my engine and python as my programming langauge”.

it’s important in order to use dictionary with a string, they need to be quoted, otherwise it’s going to throw an undefined error.

Building a hierarchy dictionary#

Now that we have a specific tool to build a hierarchy on, let’s update the code to use the proper hierarchy:

# child : parent

skeletal_hierarchy = {

"hips": None, # "root"

"spine1": "hips",

"spine2": "spine1",

"spine3": "spine2",

"neck": "spine3",

"head": "neck",

"clavicle": "spine3",

"arm": "clavicle",

"forearm": "arm",

"wrist": "forearm",

"thigh": "hips",

"calf": "thigh",

"foot": "calf",

"ball": "foot",

}Note - it follows the idea that child is on the left and parent on the right, where hips, as the root bone has value of None.

As the dictionary is ready, the next step is updating the function to use it instead of the if-ology.

import bpy

def create_skeletal_hierarchy():

armature = bpy.context.view_layer.objects.active

if armature and armature.type == 'ARMATURE':

bpy.ops.object.mode_set(mode='EDIT')

bones = armature.data.edit_bones

# child : parent

skeletal_hierarchy = {

"hips": None, # "root"

"spine1": "hips",

"spine2": "spine1",

"spine3": "spine2",

"neck": "spine3",

"head": "neck",

"clavicle": "spine3",

"arm": "clavicle",

"forearm": "arm",

"wrist": "forearm",

"thigh": "hips",

"calf": "thigh",

"foot": "calf",

"ball": "foot",

}

for bone in bones:

bone_name = bone.name.lower()

# a way to add go through all bones

# and assign them parents

# based on their dictionary value

# automatically reset to Object, to see changes in outliner

bpy.ops.object.mode_set(mode='OBJECT')

create_skeletal_hierarchy()Assigning bone parents using dictionary#

As I’ve deleted the big if-ology, the next part is actually finding a way to actually attach the bones correctly. To do that, I’ve utilized the loop that was there used before:

for bone in bones:

bone_name = bone.name.lower()bone_name exists to match the values of the dictionary even if the bone is going to be capitalized, so I can easily look if it exists in skeletal_hierarchy. If it does, I can find it’s parent as a key:value.

for bone in bones:

bone_name = bone.name.lower()

for bone_name in skeletal_hierarchy:

# note it uses [bone_name] without "",

# because it's a value that holds a string, not string itself!

parent = skeletal_hierarchy[bone_name]Now, the only thing that I need is to assign every child a parent. As I’m checking if the bone exists in the hierarchy, I can utilize that point to use bone.parent.

for bone in bones:

bone_name = bone.name.lower()

for bone_name in skeletal_hierarchy:

parent = skeletal_hierarchy[bone_name]

# checking if parent exists

# checking if parent exists in hierarchy definition

if parent and parent in skeletal_hierarchy:

# we're parentng to our actual bones list

bone.parent = bones[parent]After the addition of this part, the script looks like this:

import bpy

def create_skeletal_hierarchy():

armature = bpy.context.view_layer.objects.active

if armature and armature.type == 'ARMATURE':

bpy.ops.object.mode_set(mode='EDIT')

bones = armature.data.edit_bones

skeletal_hierarchy = {

"hips": None, # "root"

"spine1": "hips",

"spine2": "spine1",

"spine3": "spine2",

"neck": "spine3",

"head": "neck",

"clavicle": "spine3",

"arm": "clavicle",

"forearm": "arm",

"wrist": "forearm",

"thigh": "hips",

"calf": "thigh",

"foot": "calf",

"ball": "foot",

}

for bone in bones:

bone_name = bone.name.lower()

if bone_name in skeletal_hierarchy:

parent = skeletal_hierarchy[bone_name]

if parent and parent in bones:

bone.parent = bones[parent]

bpy.ops.object.mode_set(mode='OBJECT')

create_skeletal_hierarchy()Running the code on full skeleton#

This script looks much better, I can quickly change the hierarchy by updating dictionary. Everything went well unless I tried to use it on a new armature definition:

hips

spine1

spine2

spine3

neck

head

clavicle_l

arm_l

forearm_l

wrist_l

thigh_l

calf_l

foot_l

ball_l

clavicle_r

arm_r

forearm_r

wrist_r

thigh_r

calf_r

foot_r

ball_rIf you actually run this script, the hierarchy is going to look like this:

hips

spine1

spine2

spine3

neck

head

clavicle_l

arm_l

forearm_l

wrist_l

thigh_l

calf_l

foot_l

ball_l

clavicle_r

arm_r

forearm_r

wrist_r

thigh_r

calf_r

foot_r

ball_rWhy is that?

Let’s break down what is actually happening when the script goes through loops for two bones: spine3 and clavicle_l

For the spine3:

for bone in bones: # checks if spine3 exists in bones -> spine3 does# looks up the name and change spine3 to all lower case

# -> name changes to spine3

bone_name = bone.name.lower()# checks if spine3 exists in skeletal_hierarchy -> it does

if bone_name in skeletal_hierarchy:# parent becomes the value of key spine3,

# which is "spine3":"spine2" -> parent = spine2

parent = skeletal_hierarchy[bone_name]# checks if parent exists -> spine2 does

# checks if parent exists in bones -> spine2 does

if parent and parent in bones:# parent the spine3 bone to parent

# -> parent spine3 to spine2

bone.parent = bones[parent]It create a nice looking hierarchy, where spine3 is parented to spine2.

But when it evaluates clavicle_l, there’s actually a bug:

for bone in bones: # checks if clavicle_l exists in bones -> it does# looks up the name and change clavicle_l to all lower case

# -> name changes to clavicle_l

bone_name = bone.name.lower()# checks if clavicle_l exists in skeletal_hierarchy -> it does not

if bone_name in skeletal_hierarchy:At this point the rest of the code doesn’t matter, it’ll bypass it and the same thing will happen to rest of the suffixed bones. That’s the reason why final hierarchy do not parent suffixed bones at all.

Reading suffixed bones#

I am not going to lie - this part took me the longest to figue out. As a python beginner and someone who’s mostly comfortable with C, Python amazes me with so many quality-of-life functions - one of them is flexibility in working with strings.

Let’s break what is the full name of a bone:

graph LR; A[clavicle]-->B[_l];

is just

graph LR; A[base_name]-->B[suffix];

Of course there are bones without the suffix, their breakdown looks like this:

graph LR; A[spine03]-->B[" "];

That’s important, because Python’s implementation of string operations is actually super handy, let’s look at this

base_name = "clavicle"

suffix = "_l"

print(base_name + suffix) # clavicle_lThis realisation is actually wild. It fixes all the problems, as I can now:

- Take a

bone_name - Split it to it’s

base_nameandsuffix - Find parent using

base_name - Re-attach

suffixtoparent- IMPORTANT - Parent

bone_nametoparent+suffix

Point 4. is crucial - I’ve spent a lot of debugging time because I forgot to actually re-attach the suffix.

Now, to the implementation:

I’ll start with the splitting.

AS I’ve said before - Python implementaion helps a lot with the strings - each string can be used as a list of letters, so I could just check if the string ends with a suffix (thanks to endswith()), and if it did - delete it.

I’ll be adding clavicle_l and spine3 in comments to explain

for bone in bones:

name = bone.name.lower()

baseName = "" # declaration + resetting it to null

suffix = "" # declaration + resetting it to null

if name.endswith("_l"): # clavicle_l - true

baseName = name[0:-2] # clavicle

suffix = "_l" # _l

elif name.endswith("_r"): # both false

baseName = name[0:-2]

suffix = "_r"

else: # spine3 - true

baseName = name[:] # spine3

suffix = "" # ""Now that I have them split, lets find the parent(the key:value) - that’s nothing new besides declaring parent_full that we’re going to use in the next step

if base_name in skeletal_hierarchy: # clavicle / spine3

parent_base = skeletal_hierarchy[base_name] # clavicle / spine3

parent_full = "" # declaration + resetting it to nullLooking at the list, next one is the most important one - we have to re-attach suffix to the parent, that’s why I’ve created parent_full.

That’s a place where I discovered another possible bug - I had my _l or _r bones working, but clavicle_l and leg_l and their _r versions have parents, that have blank suffix, so normally,

it would look for spine3_l or hips_l and it doesn’t exist, that’s why I’ve added an elif to check if the non-suffixed version exists in bones.

if parent_base:

if parent_base + suffix in bones: # spine3_l - false, spine2 - true

parent_full = parent_base + suffix

elif parent_base in bones: # spine3 - true

parent_full = parent_base

else:

parent_full = NoneTo end the script, I have to actually parent the bones to the proper parents:

if parent_full: # spine3 - true, spine2 - true

# parent clavicle_l to spine3,

# parent spine3 to spine2

bone.parent = bones[parent_full] Aaaaaand… eureka! I finally created a script that takes bones and parent them using predefined hierarchy. Of course there are other problems that might be a good excercise to fix:

- what if there are more numbers in spine?

- What if there are prefixes instead of affixes?

I might add these cases to my script, but for the demonstration purpose let’s say that we have a set way of creating bones in our team & everyone is following the naming conventions.

Ready script#

So here it is, a script to build a game-ready skeletal hierarchy

import bpy

def create_skeletal_hierarchy():

armature = bpy.context.view_layer.objects.active

if armature and armature.type == 'ARMATURE':

bpy.ops.object.mode_set(mode='EDIT')

bones = armature.data.edit_bones

skeletal_hierarchy = {

"hips": None, # "root"

"spine1": "hips",

"spine2": "spine1",

"spine3": "spine2",

"neck": "spine3",

"head": "neck",

"clavicle": "spine3",

"arm": "clavicle",

"forearm": "arm",

"wrist": "forearm",

"thigh": "hips",

"calf": "thigh",

"foot": "calf",

"ball": "foot",

}

for bone in bones:

bone_name = bone.name.lower()

base_name = ""

suffix = ""

if bone_name.endswith("_l"):

base_name = bone_name[0:-2]

suffix = "_l"

elif bone_name.endswith("_r"):

base_name = bone_name[0:-2]

suffix = "_r"

else:

base_name = bone_name[:]

suffix = ""

if base_name in skeletal_hierarchy:

parent_base = skeletal_hierarchy[base_name]

parent_full = ""

if parent_base:

if parent_base + suffix in bones:

parent_full = parent_base + suffix

elif parent_base in bones:

parent_full = parent_base

else:

parent_full = None

if parent_full:

bone.parent = bones[parent_full]

bpy.ops.object.mode_set(mode='OBJECT')

create_skeletal_hierarchy()5. Closing thoughts#

It’s a great feeling to finally get that break-through, even though it’s a bit bitter-sweet feeling, as I’ve came up with the resolution a week too late than needed. I feel like I’ve actually learned a few new tricks and deepened my python & programming knowledge. That’s also a good momentum to work on some new stuff and get even better.

I hope that my explanation helped you as well, I am open to talking about it and see you in another tech dive!